Margaret Belcher: A Tribute from the Pugin Society

The Pugin Society was formed in 1995, with high expectations. For those of us founders who were admirers of Pugin but not in the world of academe, where could we look for nourishing information and guidance? One source was Pugin: a Gothic Passion, the publication produced by the Victoria & Albert Museum in 1994 to complement the major and influential Pugin exhibition there in that year. All the big names in the Pugin world at that time had contributed to this work, and one of them was Margaret’s. It was from reading her article ‘Pugin Writing’ in this publication that I first became aware of her as a Pugin scholar. I found the article immensely interesting and beautifully written. It became clear that the author understood Pugin perfectly and sympathetically from a literary point of view. In her final paragraph she wrote of his published work: ‘Typically Victorian in their earnest desire for social and spiritual amelioration, his publications are passionate, polemical propaganda, provocative and tendentious; they may be naïve, illogical or prejudiced upon occasion but they purvey the finest thing of all that Pugin thought of, a timeless and compelling ideal’. Many of these characteristics appear in his letters also, and it was Margaret’s innate empathy with Pugin’s vision, as expressed in this quotation, that surely made her the perfect person to undertake the massive task of editing his letters. Her professional, or ‘other’, life, as a university lecturer of nineteenth century English literature, gave her a very special understanding of the Pugin world, different to, but usefully complementing, the work of the art and architectural historians and others who make up the larger number of Pugin scholars. Indeed, Alexandra Wedgwood reports that Margaret said, in the first letter she ever received from her, 'It is in Pugin as a writer that I am interested and it is in relation to the mediaevalist literature of the Victorian period that I see him. I think he has been rather overlooked by literary historians and critics and deserves more of a place in the story of social criticism in the nineteenth century than he is usually given.'

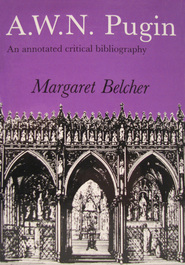

a preliminary to her magnum opus though, in addition to an article by her in 1982 about Pugin, in the Australian journal Southern Review, Margaret produced A.W.N. Pugin: an annotated critical bibliography, in 1987. All known publications by, and about, Pugin up to 1987 were catalogued by her in this book. It was far more than a catalogue, however. Each entry mentioned was summarized and commented upon in considerable detail, in pithy and insightful fashion. Indeed, the comments were such that this was a work one could just read for pure interest and entertainment. It was hugely helpful at that time for anyone wanting guidelines to find their way around the dauntingly extensive and diverse world of Pugin. I remember falling on this book with joy, its purple jacket standing out on the shelves, in a second hand bookshop in the beautiful town of Stamford, in Lincolnshire, and immediately buying it. Already it was becoming clear that Margaret was well on the way to making outstanding contributions to Pugin studies, although this was nothing compared with what was to come.

In the Introduction to the Bibliography, Margaret refers to the historian Macaulay’s vision, penned in a review of 1840, of a New Zealander sitting on London Bridge, with the city in ruins and sketching what was left of St Paul’s Cathedral. She goes on: ‘… there was a day, about 140 years later, when a New Zealander came and found that another cathedral, Pugin’s St George’s in Southwark, had been ruined. Across the river again, however, at Westminster, she saw the finest concentration of Pugin’s work in existence, shown her by England’s leading Pugin scholar [this was Alexandra Wedgwood], who stood by silent and smiling at the speechless Antipodean delight’. This moment, so vividly recorded, was perhaps a sort of Pugin epiphany for Margaret.

In the Introduction to the Bibliography, Margaret refers to the historian Macaulay’s vision, penned in a review of 1840, of a New Zealander sitting on London Bridge, with the city in ruins and sketching what was left of St Paul’s Cathedral. She goes on: ‘… there was a day, about 140 years later, when a New Zealander came and found that another cathedral, Pugin’s St George’s in Southwark, had been ruined. Across the river again, however, at Westminster, she saw the finest concentration of Pugin’s work in existence, shown her by England’s leading Pugin scholar [this was Alexandra Wedgwood], who stood by silent and smiling at the speechless Antipodean delight’. This moment, so vividly recorded, was perhaps a sort of Pugin epiphany for Margaret.

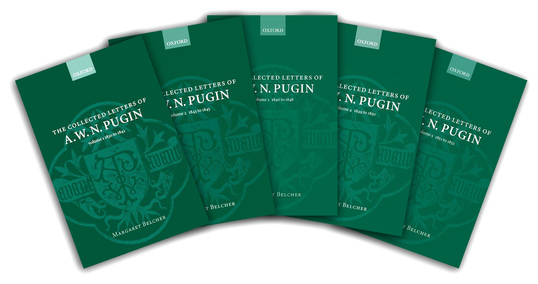

The first of the five volumes of every single known letter written by Pugin, edited by Margaret, appeared in 2001, and the last, as we probably all know, only recently, in 2015. Although the first volume came out in 2001, she had in fact been engaged upon this Herculean task from 1987 onwards, just after the publication of the Bibliography. No one could possible rate her dedication, her meticulousness, her scholarship, and not least her ability to actually read Pugin’s handwriting, any higher. She has illuminated for all Pugin scholars and admirers not only the man himself but also the world and times of her subject. Her editing is beautifully and consistently organised. Each letter is footnoted where necessary, and quite often the footnotes alone take the reader off on a whole new line of discovery, which greatly enriches the texts. The volumes of letters take Pugin through from buoyant youth, triumphs and extraordinary achievements to, ultimately, disillusion, physical and mental illness, and death. Here are revealed, in luxurious quantity, his turbulent emotional life, his humour, his heartiness, his frustrations, his friends, his enemies, his anger, his mood swings, in short all the sunshine and shadow of his wholly remarkable and unique personality. The letters are compulsive reading, and they and the editing of them are surely the definitive underpinning of Pugin studies. There is a wealth of reference here for others to draw on, concerning not only Pugin, but such subjects as, in particular, the state of the Catholic (and Anglican ) church in his day, and also the art and design of the times, political and social issues , new technology ( ‘I am such a locomotive, being always flying about’ as Pugin said) and much more. It is possible that Margaret was not a ‘believer’ in any formal sense of the word, but it is abundantly clear from her writing that she had a most sympathetic and knowledgeable understanding of Pugin’s Catholicism and of the complex, often confused, and at times turbulent, issues within the Anglican and Catholic churches during his lifetime.

Of course there are other most distinguished scholars who have also made huge contributions to Pugin studies, but it is not those with whom we are concerned on this occasion. Suffice it to say that all those who study Pugin owe a massive debt to Margaret. Her comprehensive work is now the primary point of reference for all those entering the field.

The job of tracing and collating all the known letters involved Margaret in many trips to Britain, although by no means all the letters are in the UK, some being in the USA, some in Ireland and a few even in Italy. The fact that Margaret was living as far as away as New Zealand made her achievements all the more impressive. It is amazing that, despite major earthquakes, not to mention sometimes uncertain health, the great work has been accomplished. Although computers, transcripts and microfilm helped in putting the letters together, perhaps nothing could replace the thrill of seeing the sites from whence the letters emanated, or the actual letters themselves, some beautifully, and in some cases humorously, embellished by Pugin. Margaret was enormously assisted in England in particular by the generous repeated hospitality in Worcestershire of Sarah Houle, the great great granddaughter of Pugin, and also by her London-based friend, Miss Van Noorden. The visits to England were of course for work, but they were also occasions for fun and laughter, and for adventures and expeditions shared with other great scholars and with Sarah Houle, as the latter has herself told me.

I first met Margaret in 1999 on the Pugin Society Liverpool tour. It was exciting to encounter this unassuming and naturally friendly seeming person, who entered so happily into all our excursions on that occasion, but it would not take anyone long to see that behind her disarming appearance was a razor-sharp mind and a remarkable and accurate memory for facts. She was always a strong supporter of the Pugin Society, generously supplying, without any prompting, short and pertinent articles which she knew by instinct to be just right in pitch and length for our Society journal, True Principles. What was morale boosting for us was that she appeared to feel that our organisation had real scholastic value and standing, and by her involvement with us, and her support of us, helped to make us believe that what were doing was really worthwhile. She would always answer queries, or aid in any way she could scholars and students at all levels. Only recently, indeed, she was advising Michael Fisher, Pugin expert (and provider of the photo at left), and commenting on the drafts of his forthcoming book on Pugin’s assistant and son-in-law, John Hardman Powell.

The job of tracing and collating all the known letters involved Margaret in many trips to Britain, although by no means all the letters are in the UK, some being in the USA, some in Ireland and a few even in Italy. The fact that Margaret was living as far as away as New Zealand made her achievements all the more impressive. It is amazing that, despite major earthquakes, not to mention sometimes uncertain health, the great work has been accomplished. Although computers, transcripts and microfilm helped in putting the letters together, perhaps nothing could replace the thrill of seeing the sites from whence the letters emanated, or the actual letters themselves, some beautifully, and in some cases humorously, embellished by Pugin. Margaret was enormously assisted in England in particular by the generous repeated hospitality in Worcestershire of Sarah Houle, the great great granddaughter of Pugin, and also by her London-based friend, Miss Van Noorden. The visits to England were of course for work, but they were also occasions for fun and laughter, and for adventures and expeditions shared with other great scholars and with Sarah Houle, as the latter has herself told me.

I first met Margaret in 1999 on the Pugin Society Liverpool tour. It was exciting to encounter this unassuming and naturally friendly seeming person, who entered so happily into all our excursions on that occasion, but it would not take anyone long to see that behind her disarming appearance was a razor-sharp mind and a remarkable and accurate memory for facts. She was always a strong supporter of the Pugin Society, generously supplying, without any prompting, short and pertinent articles which she knew by instinct to be just right in pitch and length for our Society journal, True Principles. What was morale boosting for us was that she appeared to feel that our organisation had real scholastic value and standing, and by her involvement with us, and her support of us, helped to make us believe that what were doing was really worthwhile. She would always answer queries, or aid in any way she could scholars and students at all levels. Only recently, indeed, she was advising Michael Fisher, Pugin expert (and provider of the photo at left), and commenting on the drafts of his forthcoming book on Pugin’s assistant and son-in-law, John Hardman Powell.

I met Margaret again in 2006, when Pugin’s house, The Grange, in Ramsgate, Kent had just opened, having been restored by an organisation called the Landmark Trust. The house could be rented, and Sarah Houle had hastened to be one of the first to take it, revelling in all its Puginesque qualities. Charateristically, she generously shared her stay with other Pugin people including Margaret, whose 70th birthday was made a celebration there on that occasion - a very special treat.

Perhaps Margaret’s apotheosis could be said to have been the time when, in 2012 she was over for the international Pugin bicenetennial conference, ‘New Directions in Gothic Revival Studies Worldwide’ at the University of Kent, organised by the University and supported by the Pugin Society. She was one of the keynote speakers, and it was my feeling that the sight of a whole auditorium filled with scholars and students whose overweening interest was Pugin and his influence, worldwide, was exhilarating to her. I think that seeing such a large audience must have made her feel justified indeed. Here was tangible proof that her labours were truly appreciated. She must have felt that she had come home. The small figure appearing on the podium showed no apprehension, only enjoyment at engaging with such an appreciative audience. She delivered a wonderfully entertaining and lively talk on Pugin’s letters, which has appeared since in somewhat modified form in our Winter 2015 Journal. The talk concluded with a moving description, all based upon the material in the letters, of Pugin at the Grange, opening the boxes containing the treasures he had designed for his Medieval Court in the Crystal Palace for the 1851 Great Exhibition. The treasures were now being returned to their owners. Margaret painted a most evocative picture of the hall at the Grange, and the awe of the servants as these remarkable objects from the Exhibition were unwrapped and displayed to view. Reporting from material in the letters, Margaret pointed out that Pugin’s wife, Jane, told him that his cook had explained, in answer to a dazed query from an onlooking servant, ‘Oh, he is one of the greatest men of England’. He certainly found one of the greatest scholars and editors to record his letters. It is good to know that the book of that Conference which is being published shortly by the University of Leuven, edited by Tim Brittain-Catlin and Jan de Maeyer, with the title Gothic Revival Worldwide, is going to be dedicated to Margaret (and also to Alexandra Wedgwood, another great Pugin scholar and Patron of the Pugin Society). Indeed Margaret had been hard at work until very recently, with two articles appearing in the most recent number of the Society’s True Principles (Spring 2016, Vol 5, No1).

There will doubtless be many obituaries of Margaret appearing in distinguished periodicals in the weeks ahead. This brief account, which comes with every sympathy for members of Margaret’s family, is however, the Pugin Society’s own tribute to her work. Her achievements were immense, and we thank her a thousand times, and more, for such outstanding, and safely accomplished, work.

Catriona Blaker, Pugin Society Committee

Perhaps Margaret’s apotheosis could be said to have been the time when, in 2012 she was over for the international Pugin bicenetennial conference, ‘New Directions in Gothic Revival Studies Worldwide’ at the University of Kent, organised by the University and supported by the Pugin Society. She was one of the keynote speakers, and it was my feeling that the sight of a whole auditorium filled with scholars and students whose overweening interest was Pugin and his influence, worldwide, was exhilarating to her. I think that seeing such a large audience must have made her feel justified indeed. Here was tangible proof that her labours were truly appreciated. She must have felt that she had come home. The small figure appearing on the podium showed no apprehension, only enjoyment at engaging with such an appreciative audience. She delivered a wonderfully entertaining and lively talk on Pugin’s letters, which has appeared since in somewhat modified form in our Winter 2015 Journal. The talk concluded with a moving description, all based upon the material in the letters, of Pugin at the Grange, opening the boxes containing the treasures he had designed for his Medieval Court in the Crystal Palace for the 1851 Great Exhibition. The treasures were now being returned to their owners. Margaret painted a most evocative picture of the hall at the Grange, and the awe of the servants as these remarkable objects from the Exhibition were unwrapped and displayed to view. Reporting from material in the letters, Margaret pointed out that Pugin’s wife, Jane, told him that his cook had explained, in answer to a dazed query from an onlooking servant, ‘Oh, he is one of the greatest men of England’. He certainly found one of the greatest scholars and editors to record his letters. It is good to know that the book of that Conference which is being published shortly by the University of Leuven, edited by Tim Brittain-Catlin and Jan de Maeyer, with the title Gothic Revival Worldwide, is going to be dedicated to Margaret (and also to Alexandra Wedgwood, another great Pugin scholar and Patron of the Pugin Society). Indeed Margaret had been hard at work until very recently, with two articles appearing in the most recent number of the Society’s True Principles (Spring 2016, Vol 5, No1).

There will doubtless be many obituaries of Margaret appearing in distinguished periodicals in the weeks ahead. This brief account, which comes with every sympathy for members of Margaret’s family, is however, the Pugin Society’s own tribute to her work. Her achievements were immense, and we thank her a thousand times, and more, for such outstanding, and safely accomplished, work.

Catriona Blaker, Pugin Society Committee

return to the NEWS