Chronological Gazetteer of the works of E.W. Pugin

By GJ Hyland – 11 March 2010 This article is undergoing continual refinement, and is updated periodically.

CATHOLIC PLACES OF WORSHIP AND ASSOCIATED PRESBYTERIES

CATHEDRALS • MONASTERY PARISH CHURCHES

• PARISH CHURCHES • CEMETERY CHAPELS

CHAPELS CONNECTED WITH COLLEGES AND INSTITUTIONS • DUAL-PURPOSE CHAPEL/SCHOOL-ROOM BUILDINGS

PRIVATE CHAPELS • CONVENT CHAPELS

CHAPELS CONNECTED WITH COLLEGES AND INSTITUTIONS • DUAL-PURPOSE CHAPEL/SCHOOL-ROOM BUILDINGS

PRIVATE CHAPELS • CONVENT CHAPELS

'These

churches were built in the tradition of the cathedrals of old, in the spirit of

sacrifice, to be temples with which to worship God - things of beauty

which are themselves Acts of Faith'

• Archbishop Downey, Forward to 'Holy Cross Church Centenary, 1849-1949', D Murray, Liverpool, 1949

The restoration of the Catholic Hierarchy in England and Wales in 1850, only two years before EW Pugin started practising, was a significant factor in accounting for the subsequent expansion in Catholic church building, necessitated, in part, particularly in the north west of England, by the great increase in the number of Irish immigrants. Ecclesiastical commissions came from both the secular clergy and the religious orders, (see Appendix III), predominant amongst which were the Benedictines and the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. Some churches were built through the munificence of members of the peerage and landed gentry, (see Appendix IV), such as the Earl of Shrewsbury and the de Trafford family, whilst others were gifts of private individuals, who, in some cases, also gave the land.

In England, more than one quarter of his churches are in the north west, the majority of these being in Lancashire (part of which is now in Merseyside, see also Appendix V). Despite a number of closures and demolitions, the Archdiocese of Liverpool still has the largest number of EW Pugin churches/chapels of any UK diocese, whilst in Ireland more churches are to be found in Co. Dublin than in any other county. His output of churches peaked over the two-year period 1863-64, during which some 22 churches/chapels were commenced.

EW Pugin's executed designs for Catholic places of worship (either alone or in partnership) totals 113, made up of three cathedrals (2 in England, 1 in Ireland), and 110 churches and chapels (including 6 dual-purpose chapel/school-room buildings) - 81 in England, 2 of which later became cathedrals, 23 in Ireland, 4 in Scotland, 1 in Wales, and 1 in Belgium, These 113 places of worship cover 16 of the present 22 archdioceses/dioceses of England & Wales, 3 of the present 8 Scottish archdioceses/dioceses, 6 of the present 26 archdioceses/dioceses of Ireland, and the diocese of Bruges (Belgium), (see Appendix VI). Almost all of them were reported on (often more than once) in contemporary architectural journals - specifically, The Builder, The Building News, The Architect and The Dublin Builder (The Irish Builder, after 1867) - in the Catholic weekly, The Tablet, and in the secular press, both local and national.

The majority of his churches are externally faced with stone, only those in the poorest areas [1] being in brick [2] , but still embellished to varying degrees - according to the available financial resources - with stone dressings/plate tracery; internally, they are, in the main, well lit, unlike some of his father's churches. In the absence of delays caused by shortage of funds, the majority of his churches took between one and two years to build, and most are still functioning as such, only 18 of the churches/chapels listed in Section A having been destroyed [3]/demolished [4]; a further 10 have been either closed or put to other uses [5].

Since the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s (and, in some cases, even before - e.g. Our Lady of Sorrows, Wrexham, St Austin, Stafford and Stanbrook Abbey), many of EW Pugin's churches have been victims of grossly insensitive internal re-ordering, so much so that, in some cases, it is now virtually impossible to envisage the original composition of their sanctuaries, with many High Altars having been severely mutilated (e.g. the cathedral at Shrewsbury and Belmont Abbey), if not completely destroyed (e.g. St Anne, Rock Ferry and Stanbrook Abbey) - actions that were never mandated by the liturgical reforms of the Council.

EW Pugin's parish churches display a vast variation in both size and opulence, ranging from Cobh Cathedral [6] in Ireland, and the English de Trafford church at Barton-on-Irwell on which no expense was spared (and which cost about 5 times that of a typical unendowed urban church of comparable size), to those [7] he designed for much less well-endowed, often highly impoverished, working-class congregations, such as at Our Lady of Reconciliation, Liverpool, St Ann, Ashton-under-Lyne, St Marie, Widnes and St Patrick, Peel. Here, as he once said, he was often compelled to show what he could not do, rather than what he could; frequently, every point of design, every corner, feature (that he wished to see produced) had, in the end, to be sacrificed to necessity - simply for want of means [8]; indeed, in some cases, it is difficult to believe that the designs came from the pen of EW Pugin!

• Archbishop Downey, Forward to 'Holy Cross Church Centenary, 1849-1949', D Murray, Liverpool, 1949

The restoration of the Catholic Hierarchy in England and Wales in 1850, only two years before EW Pugin started practising, was a significant factor in accounting for the subsequent expansion in Catholic church building, necessitated, in part, particularly in the north west of England, by the great increase in the number of Irish immigrants. Ecclesiastical commissions came from both the secular clergy and the religious orders, (see Appendix III), predominant amongst which were the Benedictines and the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. Some churches were built through the munificence of members of the peerage and landed gentry, (see Appendix IV), such as the Earl of Shrewsbury and the de Trafford family, whilst others were gifts of private individuals, who, in some cases, also gave the land.

In England, more than one quarter of his churches are in the north west, the majority of these being in Lancashire (part of which is now in Merseyside, see also Appendix V). Despite a number of closures and demolitions, the Archdiocese of Liverpool still has the largest number of EW Pugin churches/chapels of any UK diocese, whilst in Ireland more churches are to be found in Co. Dublin than in any other county. His output of churches peaked over the two-year period 1863-64, during which some 22 churches/chapels were commenced.

EW Pugin's executed designs for Catholic places of worship (either alone or in partnership) totals 113, made up of three cathedrals (2 in England, 1 in Ireland), and 110 churches and chapels (including 6 dual-purpose chapel/school-room buildings) - 81 in England, 2 of which later became cathedrals, 23 in Ireland, 4 in Scotland, 1 in Wales, and 1 in Belgium, These 113 places of worship cover 16 of the present 22 archdioceses/dioceses of England & Wales, 3 of the present 8 Scottish archdioceses/dioceses, 6 of the present 26 archdioceses/dioceses of Ireland, and the diocese of Bruges (Belgium), (see Appendix VI). Almost all of them were reported on (often more than once) in contemporary architectural journals - specifically, The Builder, The Building News, The Architect and The Dublin Builder (The Irish Builder, after 1867) - in the Catholic weekly, The Tablet, and in the secular press, both local and national.

The majority of his churches are externally faced with stone, only those in the poorest areas [1] being in brick [2] , but still embellished to varying degrees - according to the available financial resources - with stone dressings/plate tracery; internally, they are, in the main, well lit, unlike some of his father's churches. In the absence of delays caused by shortage of funds, the majority of his churches took between one and two years to build, and most are still functioning as such, only 18 of the churches/chapels listed in Section A having been destroyed [3]/demolished [4]; a further 10 have been either closed or put to other uses [5].

Since the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s (and, in some cases, even before - e.g. Our Lady of Sorrows, Wrexham, St Austin, Stafford and Stanbrook Abbey), many of EW Pugin's churches have been victims of grossly insensitive internal re-ordering, so much so that, in some cases, it is now virtually impossible to envisage the original composition of their sanctuaries, with many High Altars having been severely mutilated (e.g. the cathedral at Shrewsbury and Belmont Abbey), if not completely destroyed (e.g. St Anne, Rock Ferry and Stanbrook Abbey) - actions that were never mandated by the liturgical reforms of the Council.

EW Pugin's parish churches display a vast variation in both size and opulence, ranging from Cobh Cathedral [6] in Ireland, and the English de Trafford church at Barton-on-Irwell on which no expense was spared (and which cost about 5 times that of a typical unendowed urban church of comparable size), to those [7] he designed for much less well-endowed, often highly impoverished, working-class congregations, such as at Our Lady of Reconciliation, Liverpool, St Ann, Ashton-under-Lyne, St Marie, Widnes and St Patrick, Peel. Here, as he once said, he was often compelled to show what he could not do, rather than what he could; frequently, every point of design, every corner, feature (that he wished to see produced) had, in the end, to be sacrificed to necessity - simply for want of means [8]; indeed, in some cases, it is difficult to believe that the designs came from the pen of EW Pugin!

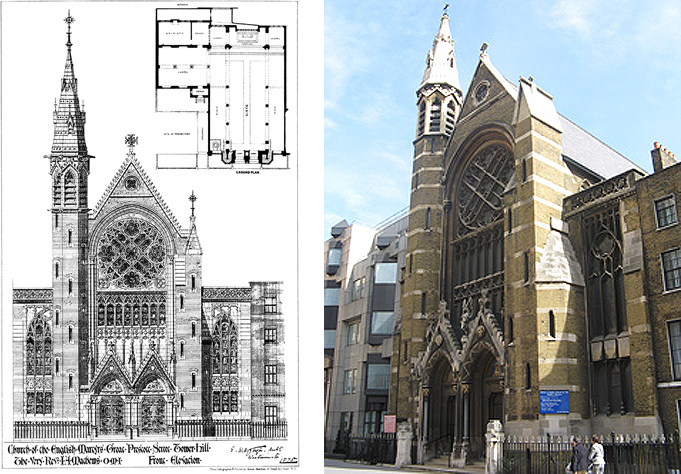

Many churches in poorer areas were opened prematurely, there being insufficient funds to permit their completion; in one case, Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Harwich, only one half of the projected design could be afforded at the time of opening. It could be many years before completion was possible - in some cases, not until after EW Pugin's death; but the original designs were usually adhered to. After EW Pugin's death in 1875, his younger brother, Cuthbert Welby (1840-1928) and half-brother, Edmund Peter (1851-1904, invariably known as 'Peter Paul' (PP) [9]) oversaw the completion of churches that had already been begun, namely English Martyrs, Tower Hill, Our Lady, Workington, St Mary, Warrington and St Anne, Rock Ferry, and later (under the style of Pugin & Pugin [10]) were frequently engaged to extend churches that had been originally completed by EW Pugin, often resulting in an improvement, particularly in the area of the sanctuary, as, for example, at English Martyrs, Preston.

Some churches, however, remain incomplete to this day, particularly with respect to carving, e.g. Our Lady & All Saints, Stourbridge, and to projected towers and spires, e.g. Our Lady, Birkenhead. It is important to bear these privations in mind when assessing (i) the indictment that EW Pugin was a 'wildly uneven architect', ref. xv, and (ii) the often disparaging, petty and unsympathetic remarks of Pevsner, ref. ii, such as his descriptions of some interiors as 'starved'.

Some churches, however, remain incomplete to this day, particularly with respect to carving, e.g. Our Lady & All Saints, Stourbridge, and to projected towers and spires, e.g. Our Lady, Birkenhead. It is important to bear these privations in mind when assessing (i) the indictment that EW Pugin was a 'wildly uneven architect', ref. xv, and (ii) the often disparaging, petty and unsympathetic remarks of Pevsner, ref. ii, such as his descriptions of some interiors as 'starved'.

|

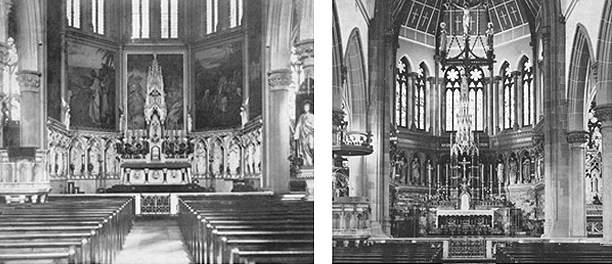

One justifiable criticism, however, that can be made of the interiors of some of EW Pugin's churches - particularly the smaller ones - is that they are marred by the pillars of the nave arcades being disproportionately short in comparison with the height of connecting arches and surmounting clerestory, creating an impression of 'top-heaviness', the pillars appearing to have partially sunk into the floor of the nave (particularly once the benches are in position [11] ). In the absence of a clerestory, on the other hand, the problem can be the converse, the pillars sometimes appearing disproportionately long, partly because of their slenderness; these two extremes are illustrated in the following photographs (that show, in addition, examples of what Pevsner describes as EW Pugin's 'summary' capitals).

Despite, these criticisms, however, he invariably succeeded in producing, even in the most deprived areas, dignified places of worship that became the focal point of the Catholic community, and which were very often the only place of beauty in the locality to which people of all classes had access, and in which they could take justifiable pride, and with which - as opposed to simply in which - they could worship in a correspondingly dignified way. |

|

The plain and unadorned exterior of some of the poorer churches often belies, however, the impressiveness of their interiors, although in some cases this is a result improvements and adornments that post-date their opening, often by many years. In many cases, Pugin & Pugin furnished EW Pugin churches with permanent altars [12] and reredoses that complete their sanctuaries in perfect keeping with their brother's original designs - an activity in which PP Pugin specialised and excelled [13], and in whose hands, the so-called 'Benediction Altar' reached its apogee (see Appendix VII).

It is important to bear these privations in mind when assessing (i) the indictment that EW Pugin was a 'wildly uneven architect', ref. xv, and (ii) the often disparaging, petty and unsympathetic remarks of Pevsner, ref. ii, such as his descriptions of some interiors as 'starved'.

One justifiable criticism, however, that can be made of the interiors of some of EW Pugin's churches - particularly the smaller ones - is that they are marred by the pillars of the nave arcades being disproportionately short in comparison with the height of connecting arches and surmounting clerestory, creating an impression of 'top-heaviness', the pillars appearing to have partially sunk into the floor of the nave (particularly once the benches are in position [11]). In the absence of a clerestory, on the other hand, the problem can be the converse, the pillars sometimes appearing disproportionately long, partly because of their slenderness; these two extremes are illustrated in the following photographs (that show, in addition, examples of what Pevsner describes as EW Pugin's 'summary' capitals).

It is important to bear these privations in mind when assessing (i) the indictment that EW Pugin was a 'wildly uneven architect', ref. xv, and (ii) the often disparaging, petty and unsympathetic remarks of Pevsner, ref. ii, such as his descriptions of some interiors as 'starved'.

One justifiable criticism, however, that can be made of the interiors of some of EW Pugin's churches - particularly the smaller ones - is that they are marred by the pillars of the nave arcades being disproportionately short in comparison with the height of connecting arches and surmounting clerestory, creating an impression of 'top-heaviness', the pillars appearing to have partially sunk into the floor of the nave (particularly once the benches are in position [11]). In the absence of a clerestory, on the other hand, the problem can be the converse, the pillars sometimes appearing disproportionately long, partly because of their slenderness; these two extremes are illustrated in the following photographs (that show, in addition, examples of what Pevsner describes as EW Pugin's 'summary' capitals).

|

|

Despite these criticisms, however, he succeeded in producing dignified places of worship that became the focal point of the Catholic community, and which were very often the only place of beauty in the locality to which people of all classes had access, and in which they could take justifiable pride, and with which - as opposed to simply in which - they could worship in a correspondingly dignified way.

The plain, unadorned exterior of some churches often belies the impressiveness of their interiors, although in some cases these features post-date their opening. In some cases, Pugin & Pugin furnished EW Pugin churches with permanent altars [12] and reredoses that complete their sanctuaries in keeping with their brother's original designs - an activity in which PP Pugin excelled [13], and in whose hands, the 'Benediction Altar' reached its apogee (see Appendix VII). |

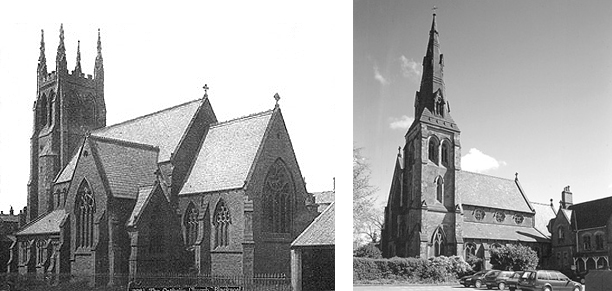

Three distinct phases of development are discernible in EW Pugin's oeuvre, particularly in England. The first of these (which lasted from 1852 to about 1859, and comprises some 24 realised places of worship) is characterised by a style that is broadly similar to that on which his father eventually settled, namely, 14th century English Decorated Gothic (or 'second pointed') [14], in which a clear distinction is maintained between nave and chancel, the latter being square-ended and usually under a lower roof line.

Evidence of a more idiosyncratic approach can, however, be discerned as early as 1856, when his predilection for W. end bell-cotes - more dramatic and original than either those of his father (such as at St Mary, Warwick Bridge, and St John, Alton) or those of his own earlier, more restrained essays, such as those at Shrewsbury cathedral and St Mary's Abbey, Oulton - first manifested itself at St Vincent de Paul, Liverpool.

Evidence of a more idiosyncratic approach can, however, be discerned as early as 1856, when his predilection for W. end bell-cotes - more dramatic and original than either those of his father (such as at St Mary, Warwick Bridge, and St John, Alton) or those of his own earlier, more restrained essays, such as those at Shrewsbury cathedral and St Mary's Abbey, Oulton - first manifested itself at St Vincent de Paul, Liverpool.

Exceptions to the lower roofed, square-ended chancels that predominate in this first phase are to be found at Our Lady, Childwall and the basilica at Dadizele, which prefigure the dominant, innovative design of his second phase (vide infra).

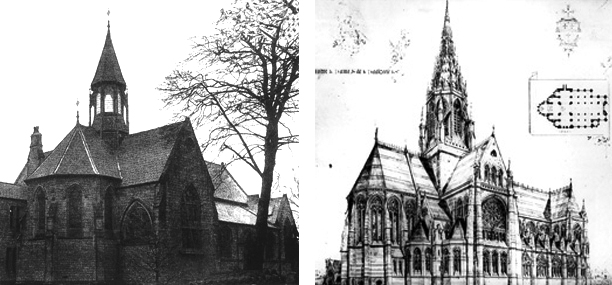

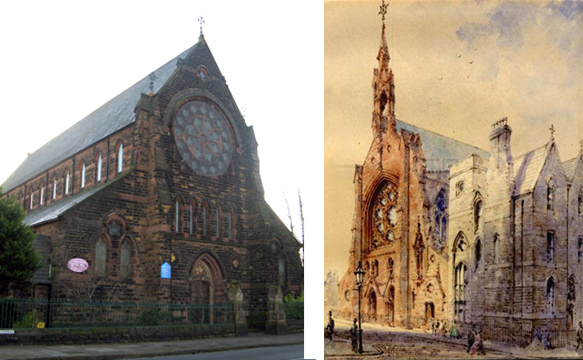

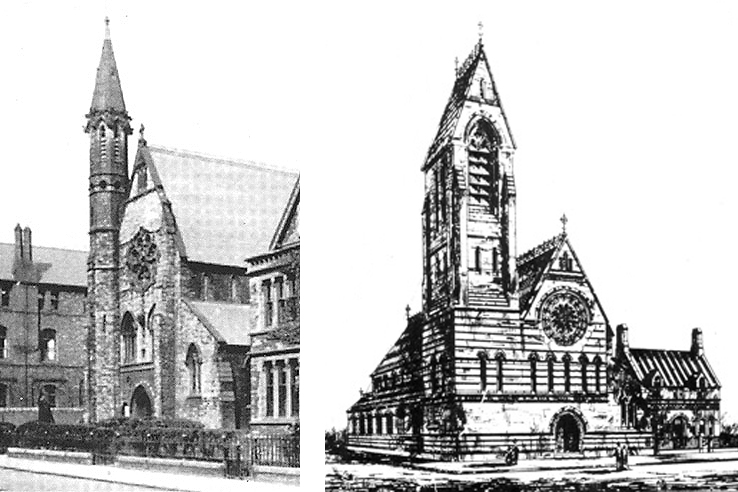

The second, and most prolific phase (which spanned the years 1859-c.1869/70, and comprises some 75 realised churches/chapels) was heralded by the design of his Liverpool church of Our Lady of Reconciliation (in the earlier 13th century Geometric Gothic), which utilises elements of the 2 churches illustrated in Fig.14 in a novel attempt to reconcile Gothic with a central requirement of the counter-reformation Tridentine liturgy, namely that the High Altar be clearly visible to the majority of the congregation, not only in connection with the Mass, but also for Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament and the service of Quarant' ore (an exposition of the Blessed Sacrament for 40 hours), both of which were becoming very popular at this time, and which the recently re-established hierarchy was keen to promote. EW Pugin achieved this reconciliation by using wide nave arcades with slender pillars (to facilitate good sight-lines), and by replacing the deep chancel of the displaced Sarum Rite by a quite shallow apsidal sanctuary that is essentially a continuation of the nave under the same roof-line, with no demarcation between them, either internally or externally. Externally, this results (in the absence of transepts) in a kind of (inverted) 'vessel' [17] church; interiorally, the roof principals are reminiscent of the rib-frame of the hull of a wooden vessel.

The second, and most prolific phase (which spanned the years 1859-c.1869/70, and comprises some 75 realised churches/chapels) was heralded by the design of his Liverpool church of Our Lady of Reconciliation (in the earlier 13th century Geometric Gothic), which utilises elements of the 2 churches illustrated in Fig.14 in a novel attempt to reconcile Gothic with a central requirement of the counter-reformation Tridentine liturgy, namely that the High Altar be clearly visible to the majority of the congregation, not only in connection with the Mass, but also for Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament and the service of Quarant' ore (an exposition of the Blessed Sacrament for 40 hours), both of which were becoming very popular at this time, and which the recently re-established hierarchy was keen to promote. EW Pugin achieved this reconciliation by using wide nave arcades with slender pillars (to facilitate good sight-lines), and by replacing the deep chancel of the displaced Sarum Rite by a quite shallow apsidal sanctuary that is essentially a continuation of the nave under the same roof-line, with no demarcation between them, either internally or externally. Externally, this results (in the absence of transepts) in a kind of (inverted) 'vessel' [17] church; interiorally, the roof principals are reminiscent of the rib-frame of the hull of a wooden vessel.

|

In his (medium-sized) church in Warwick, commenced a few months after Our Lady of Reconciliation, Liverpool, the entire nave arcade consists of only 3 wide bays, each wide enough to accommodate 2 clerestory windows, whilst the aisles are reduced to passages with no seating.

|

As has been repeatedly stressed by R O'Donnell [18], this solution (in which the then Bishop of Liverpool, the Rt Rev Dr Alexander Goss actively participated, even making suggestions as to how it might best be achieved at the least cost [19]) marked a revolution in Catholic church design, and was one that EW Pugin continued to develop and refine for the next 10 years, until the end of the 1860s.

|

|

One such later development was to mark the nave/sanctuary junction by a sudden reduction in the width of the most eastern bay of the nave arcade, and to incorporate nearby bilateral gabled clerestory windows (often in mini-rose form) that externally give the impression of embryonic transepts [20]. It was during this second phase that the influence of Franco-Flemish Gothic became increasingly evident.

As already noted, sanctuaries of this phase are usually (but not invariably - vide infra) contained within an apsidal E. end that was, at first, semicircular (Fig.15a), but subsequently usually semi-octagonal (as in AWN Pugin's St Chad, Birmingham and St Mary, Derby). In some cases, the sanctuary is lit by groups of short lancets at clerestory level above blank walls against which sits the reredos without interfering with the light. |

In other cases, the apsidal E. end is lit by much longer (traceried) windows that are often externally gabled, such as at All Saints, Barton-upon-Irwell (Fig.42b) and St Gregory, Longton.

Typical of this second phase of development is the tripartite composition of the W. front, formed by positioning buttresses where the walls of the nave meet the W. wall. Centrally located between the buttresses is usually the principal door, above which is often a deeply recessed rose/wheel window (sometimes set above a row of short lancets), the apex of the W. gable being surmounted either by a metal cross, or by an elaborate bell-cote that usually itself supports a tall (floriated) metal cross.

Typical of this second phase of development is the tripartite composition of the W. front, formed by positioning buttresses where the walls of the nave meet the W. wall. Centrally located between the buttresses is usually the principal door, above which is often a deeply recessed rose/wheel window (sometimes set above a row of short lancets), the apex of the W. gable being surmounted either by a metal cross, or by an elaborate bell-cote that usually itself supports a tall (floriated) metal cross.

Of the 39 projected bell-cotes for churches/chapels that were actually built, 37 [23] were realised, the vast majority belonging to category (a). A complete inventory of EW Pugin's bell-cotes (both realised & unrealised) can be found in Appendix VIII.

Although a bell-cote was a more affordable option/substitute for a belfry housed in a tower, particularly when the tower was surmounted by a spire, the number of towers (spired or otherwise) projected (for churches that were actually built) exceeds the number of projected bell-cotes by five. Of the 44 spires projected (for churches that were actually built), only 15 were ever built [24].

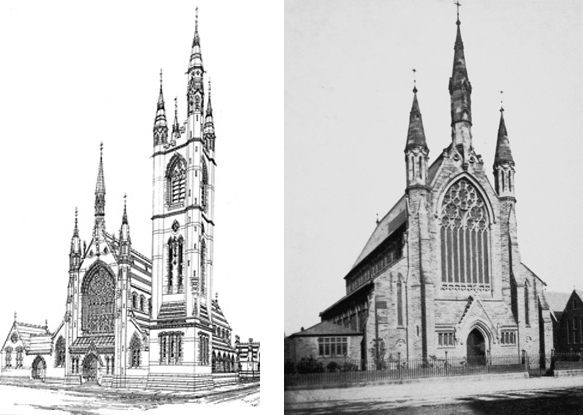

Four distinct generic spire types can be discerned in the oeuvre of EW Pugin - see Fig.22: a) a broach spire; b) a semi-broach spire - i.e. a spire whose broaches are detached from the central octagonal spire, taking the form of angle finials of tapering triangular cross-section; c) a spire of octagonal cross-section, the base of which is surrounded by four pinnacled angle-turrets; d) a Franco-Flemish (chisel-shaped) spire of tapering rectangular cross-section. There are seven realised instances [25] of (a); two realised instances [26] of (b); four realised instances [27] of (c), all of which are essentially minor variations on the formula [28] shown in Fig. 22c; one realised [29] instance of (d).

Whilst the broach spire features in both the first and second phases of EW Pugin's development, the realised instances of the other three types [30] are exclusive to the second phase.

Although a bell-cote was a more affordable option/substitute for a belfry housed in a tower, particularly when the tower was surmounted by a spire, the number of towers (spired or otherwise) projected (for churches that were actually built) exceeds the number of projected bell-cotes by five. Of the 44 spires projected (for churches that were actually built), only 15 were ever built [24].

Four distinct generic spire types can be discerned in the oeuvre of EW Pugin - see Fig.22: a) a broach spire; b) a semi-broach spire - i.e. a spire whose broaches are detached from the central octagonal spire, taking the form of angle finials of tapering triangular cross-section; c) a spire of octagonal cross-section, the base of which is surrounded by four pinnacled angle-turrets; d) a Franco-Flemish (chisel-shaped) spire of tapering rectangular cross-section. There are seven realised instances [25] of (a); two realised instances [26] of (b); four realised instances [27] of (c), all of which are essentially minor variations on the formula [28] shown in Fig. 22c; one realised [29] instance of (d).

Whilst the broach spire features in both the first and second phases of EW Pugin's development, the realised instances of the other three types [30] are exclusive to the second phase.

|

The only spire designs that do not conform with any of these 4 types are those at the basilica at Dadizele (Fig.14b), St Aloysius, Durham (Fig.39a), Our Lady, Birkenhead (Fig.9a), St Austin, Stafford (Fig.128), and Stanbrook Abbey (Fig.46a).

Premièred in this second phase at St Alexander, Bootle (Fig.23a) was the slender octagonal tower terminating in a spirelet [31], a formula that was later re-used in his third phase at English Martyrs, Tower Hill (Fig.27), whilst unique to the second phase was the steeply pitched saddle-backed tower projected for Wolverhampton (Fig.23b), but never realised. A gallery of EW Pugin's spires and towers (both realised & unrealised) can be found in Appendix IX. Although the design of the majority of the churches belonging to EW Pugin's second phase follow the inverted 'vessel' formula premièred at Our Lady of Reconciliation, Liverpool, he reverts, on occasion (such as at Stourbridge and at Birkdale), to the lower roofed square-ended chancels characteristic of his first phase. A novel variation on the tripartite W. front formula described above is to be found at English Martyrs, Preston (Fig. 25), together with the projected W. front elevation. It is mainly designs from this second phase that have attracted appellations such as 'nervous', ref. v and 'spiky', ref. xiii, and the allusion that they even display 'rogue' elements, ref. x. |

|

EW Pugin's third

and final phase (c.1869/70-75, comprising only ten churches/chapels) is

characterized by a return to a greater degree of sobriety, redolent of his

first period, and marked by a reversion to square-ended chancels, usually of a different [32] height

from the nave [33], the

junction of which is demarcated by a prominent chancel arch. Furthermore, the

familiar W. end rose/wheel window and the lancet-like apse windows that

characterise the second phase of development are often now interchanged, whilst

(with the exception of St Joseph, Nechells and Our Lady, Workington) the

bell-cote is abandoned in favour of an off-centre tower/spire (Fig. 26).

Of the towers of this period, only one (English Martyrs, Tower Hill) was completed as intended, the design of which was pre-figured by that of St Alexander, Bootle (Fig.23a) belonging to EW Pugin's second phase.

Of the towers of this period, only one (English Martyrs, Tower Hill) was completed as intended, the design of which was pre-figured by that of St Alexander, Bootle (Fig.23a) belonging to EW Pugin's second phase.

At the time of EW Pugin's premature death in 1875, a number of churches and associated ecclesiastical building were in the course of erection, the final church to be commenced under his direction being St Anne's, Rock Ferry, and the last building inspected (on the day of his death) being the Juniorate College at Kilburn, both for the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. These and the other unfinished churches at Tower Hill, Workington and Warrington (and those in the course of being extended - such as Holy Cross, Liverpool, and Our Lady's, Birkenhead) were brought to completion initially by his brother Cuthbert Welby and half-brother Peter Paul, who were subsequently joined (from about 1877 until about 1880) by GC Ashlin, in the partnership Pugin, Ashlin & Pugin; after Ashlin's departure, the firm became Pugin & Pugin, and survived until the death of Charles HC Purcell (see note 10 below and Appendix I) in 1958.

Over the 23 years of his career, EW Pugin's designs for Catholic places of worship constitute, by far, the most numerous genre of his entire canon; these designs naturally separate into 8 categories, specifically: Cathedrals, Parish Churches (distinguishing those attached to monastic foundations), Cemetery Chapels, Chapels connected with Colleges & Institutions, Dual-purpose Chapel/School-room buildings, Private Chapels & Convent Chapels. The Gazetteer entries in each category are prefaced with illustrated introductions that highlight specific points of architectural interest and relevance, and in which attention is drawn to intra & inter-genre stylistic similarities and interconnections that it has so far been possible to discern.

Domine, dilexi decorum domus tuae, et locum habitationis gloriae tuae - Ps XXV

NOTES

1 • In this respect, St Joseph, Birkdale constitutes something of an exception.

2 • In the cases of St Francis, Gorton and the basilica at Dadizele, brick (but with generous stone dressings) was deliberately used in order to conform to ancient church building practice in Belgium, Dadizele being in Belgium, whilst St Francis, Gorton was founded and built by Belgian friars.

3 • Occasionally by natural forces, e.g. St Gregory, Longton and Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Harwich, but more often by bombing during the Second World War, e.g. Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Kensington and St Alexander, Bootle.

4 • On the instructions of members of the RC Hierarchy, e.g. at Our Lady Immaculate, Everton and St Peter, Greengate, Salford.

5 • For example St Marie, Widnes and Euxton chapel.

6 • By the time it was completed in 1915, 47 years after the laying of its Foundation Stone, this cathedral had cost in excess of one quarter of a million pounds; was more than any other building in Ireland cost up to that time.

7 • These could be very small (costing only a few hundred pounds) and capable of accommodating only a few hundred worshippers.

8 • Centenary Brochure of the Church of St Thomas of Canterbury & the English Martyrs, Preston.

9 • Having been born on the Feast of Ss Peter & Paul, he took the name Paul at his Confirmation.

10 • Around 1876 until about 1880, CW & PP Pugin went into partnership with GC Ashlin under the style Pugin, Ashlin & Pugin; thereafter, the firm became known as Pugin & Pugin, PP Pugin being the active partner, Cuthbert remaining reclusively in Ramsgate. After the death of PP Pugin in 1904, the firm continued with CW Pugin as sleeping partner, Sebastian Pugin Powell (1866-1949, a son of John Hardman Powell & Anne Pugin) as head of the London office (at 159 Kensington High St) and his cousin Charles HC Purcell (1874-1958 - see Appendix I under Ashlin) as head of the Liverpool office (finally at Harley Buildings, 11 Old Hall St, Liverpool, 3) in partnership with S Stevenson-Jones; Pugin & Pugin ceased to exist after Purcell's death in 1958.

11 • This defect is one that is shared by some of his father's churches, such as that at Brewood.

12 • Often, the first altars were but temporary wooden structures, which, prior to the building of the chancel, were erected in front of a temporary wall at the E. extremity of the completed nave.

13 • In the case of some of PP Pugin's early commissions it is impossible to establish whether the designs were his own, or whether he was only elaborating/implementing those already prepared by EW Pugin before his death; in support of the latter is the fact that elements typical of EW Pugin's altars appear in some of the early altars designed by PP Pugin.

14 • Dating from the reigns of Edward I, II & III - i.e. 1272-1377.

15 • The W. tower shown in Fig. 12a is (with the exception of that at Stanbrook Abbey (Fig. 46b) the only realised instance of an embattled design in EW Pugin's entire output.

16 • See Appendix VII.

17 • Indeed, the term 'nave' comes from navis, the Latin for ship/vessel/boat.

18 • e.g. ref. vii.

19 • Letter Books of Bishop Goss, 1856-72, Lancashire Record Office, Preston.

20 • In the case of the Friary church at Gorton there is a double gable on each side.

21 • Above the adjacent arch can be seen the window in the embryonic transept gable, shown externally at another location in Fig.17b.

22 • An interesting synthesis of types (a) and (b) is to be found at Ratcliffe College chapel (Fig.91).

23 • Two were not to the original design, namely those at St Francis, Gorton and St Begh, Whitehaven.

24 • The highest proportion of completed spires is in Ireland (8 out of 16, i.e. 50%, compared with only 8 out of 24 (33%) in the UK).

25 • At Our Lady of Sorrows, Wrexham, Our Lady, Great Harwood, Assumption, Our Lady's Island, St Patrick, Monkstown, Co Dublin, Sacred Heart, Arles, Sacred Heart, Ferrybank and St Catherine, Kingsdown.

26 • At Ss Peter & Paul, Kilanerin and St Mary, Listowel.

27 • The spire of the church at Monkstown, Co Cork has angle turrets, but these do not feature in the original design of Pugin & Ashlin, which shows, instead, a broach spire. Since the existing spire post-dates EW Pugin's death, it could well be by Ashlin, a conjecture that is supported on stylistic grounds. The 4 other cases are St Ann, Stretford, Our Lady & All Saints, Stourbridge, St Mary, Barrow-in-Furness and St Patrick, Fermoy.

28 • The best example of this kind (in respect of the balance between the heights of the spire and supporting tower) is that projected, but unrealised, at Tralee (Fig.117).

29 • At Ss Augustine & John, Dublin; the second (in a secular/domestic context) is at Scarisbrick Hall, Lancs (Fig.123).

30 • Angle-turreted spires had been projected in some designs of his first phase e.g. St Edward's Cathedral, Liverpool (Fig.106), but none were realised.

31 • Redolent of the Irish 'round tower' but is here of octagonal cross-section.

32 • St Mary, Warrington is an exception to this.

33 • In the case of EW Pugin's final church, St Anne, Rock Ferry, the roof level of the chancel is actually higher than the nave, which, unusually for him, was aisleless - as also is St Kevin, Dublin.

34 • The chancel shown in Fig.26a was figured interiorally at Our Lady, Workington, and externally at Ss Mary & Finnan, Glenfinnan.

Over the 23 years of his career, EW Pugin's designs for Catholic places of worship constitute, by far, the most numerous genre of his entire canon; these designs naturally separate into 8 categories, specifically: Cathedrals, Parish Churches (distinguishing those attached to monastic foundations), Cemetery Chapels, Chapels connected with Colleges & Institutions, Dual-purpose Chapel/School-room buildings, Private Chapels & Convent Chapels. The Gazetteer entries in each category are prefaced with illustrated introductions that highlight specific points of architectural interest and relevance, and in which attention is drawn to intra & inter-genre stylistic similarities and interconnections that it has so far been possible to discern.

Domine, dilexi decorum domus tuae, et locum habitationis gloriae tuae - Ps XXV

NOTES

1 • In this respect, St Joseph, Birkdale constitutes something of an exception.

2 • In the cases of St Francis, Gorton and the basilica at Dadizele, brick (but with generous stone dressings) was deliberately used in order to conform to ancient church building practice in Belgium, Dadizele being in Belgium, whilst St Francis, Gorton was founded and built by Belgian friars.

3 • Occasionally by natural forces, e.g. St Gregory, Longton and Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Harwich, but more often by bombing during the Second World War, e.g. Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Kensington and St Alexander, Bootle.

4 • On the instructions of members of the RC Hierarchy, e.g. at Our Lady Immaculate, Everton and St Peter, Greengate, Salford.

5 • For example St Marie, Widnes and Euxton chapel.

6 • By the time it was completed in 1915, 47 years after the laying of its Foundation Stone, this cathedral had cost in excess of one quarter of a million pounds; was more than any other building in Ireland cost up to that time.

7 • These could be very small (costing only a few hundred pounds) and capable of accommodating only a few hundred worshippers.

8 • Centenary Brochure of the Church of St Thomas of Canterbury & the English Martyrs, Preston.

9 • Having been born on the Feast of Ss Peter & Paul, he took the name Paul at his Confirmation.

10 • Around 1876 until about 1880, CW & PP Pugin went into partnership with GC Ashlin under the style Pugin, Ashlin & Pugin; thereafter, the firm became known as Pugin & Pugin, PP Pugin being the active partner, Cuthbert remaining reclusively in Ramsgate. After the death of PP Pugin in 1904, the firm continued with CW Pugin as sleeping partner, Sebastian Pugin Powell (1866-1949, a son of John Hardman Powell & Anne Pugin) as head of the London office (at 159 Kensington High St) and his cousin Charles HC Purcell (1874-1958 - see Appendix I under Ashlin) as head of the Liverpool office (finally at Harley Buildings, 11 Old Hall St, Liverpool, 3) in partnership with S Stevenson-Jones; Pugin & Pugin ceased to exist after Purcell's death in 1958.

11 • This defect is one that is shared by some of his father's churches, such as that at Brewood.

12 • Often, the first altars were but temporary wooden structures, which, prior to the building of the chancel, were erected in front of a temporary wall at the E. extremity of the completed nave.

13 • In the case of some of PP Pugin's early commissions it is impossible to establish whether the designs were his own, or whether he was only elaborating/implementing those already prepared by EW Pugin before his death; in support of the latter is the fact that elements typical of EW Pugin's altars appear in some of the early altars designed by PP Pugin.

14 • Dating from the reigns of Edward I, II & III - i.e. 1272-1377.

15 • The W. tower shown in Fig. 12a is (with the exception of that at Stanbrook Abbey (Fig. 46b) the only realised instance of an embattled design in EW Pugin's entire output.

16 • See Appendix VII.

17 • Indeed, the term 'nave' comes from navis, the Latin for ship/vessel/boat.

18 • e.g. ref. vii.

19 • Letter Books of Bishop Goss, 1856-72, Lancashire Record Office, Preston.

20 • In the case of the Friary church at Gorton there is a double gable on each side.

21 • Above the adjacent arch can be seen the window in the embryonic transept gable, shown externally at another location in Fig.17b.

22 • An interesting synthesis of types (a) and (b) is to be found at Ratcliffe College chapel (Fig.91).

23 • Two were not to the original design, namely those at St Francis, Gorton and St Begh, Whitehaven.

24 • The highest proportion of completed spires is in Ireland (8 out of 16, i.e. 50%, compared with only 8 out of 24 (33%) in the UK).

25 • At Our Lady of Sorrows, Wrexham, Our Lady, Great Harwood, Assumption, Our Lady's Island, St Patrick, Monkstown, Co Dublin, Sacred Heart, Arles, Sacred Heart, Ferrybank and St Catherine, Kingsdown.

26 • At Ss Peter & Paul, Kilanerin and St Mary, Listowel.

27 • The spire of the church at Monkstown, Co Cork has angle turrets, but these do not feature in the original design of Pugin & Ashlin, which shows, instead, a broach spire. Since the existing spire post-dates EW Pugin's death, it could well be by Ashlin, a conjecture that is supported on stylistic grounds. The 4 other cases are St Ann, Stretford, Our Lady & All Saints, Stourbridge, St Mary, Barrow-in-Furness and St Patrick, Fermoy.

28 • The best example of this kind (in respect of the balance between the heights of the spire and supporting tower) is that projected, but unrealised, at Tralee (Fig.117).

29 • At Ss Augustine & John, Dublin; the second (in a secular/domestic context) is at Scarisbrick Hall, Lancs (Fig.123).

30 • Angle-turreted spires had been projected in some designs of his first phase e.g. St Edward's Cathedral, Liverpool (Fig.106), but none were realised.

31 • Redolent of the Irish 'round tower' but is here of octagonal cross-section.

32 • St Mary, Warrington is an exception to this.

33 • In the case of EW Pugin's final church, St Anne, Rock Ferry, the roof level of the chancel is actually higher than the nave, which, unusually for him, was aisleless - as also is St Kevin, Dublin.

34 • The chancel shown in Fig.26a was figured interiorally at Our Lady, Workington, and externally at Ss Mary & Finnan, Glenfinnan.